Ultimate Guide to Chalcedony

Chalcedony is a cryptocrystalline form of silica, and often the subject of much debate among rockhounds. While it’s simple to define, it’s also associated with only a few types of stones despite the truly diverse array of different chalcedony forms found in nature. You just have to take a peek under the hood to see why that’s the case.

So, without further ado, let’s drop right in and we’ll teach you a bit about it in our guide to chalcedony.

What is Chalcedony?

Chalcedony is a cryptocrystalline form of silica.

Cryptocrystalline compounds are those that have such a fine intergrowth of crystals that it’s not even apparent under magnification that the material is crystallized. It can be seen only in thin sections with proper backlighting and high magnification.

Chalcedony, by itself, isn’t really a mineral. The cryptocrystalline structure of the stone is made up of the intergrowth of two different forms of silica: quartz and moganite. Moganite is very similar to quartz, with a slight differing crystal structure.

These two forms grow into each other and create our chalcedony.

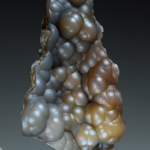

In its purest form, chalcedony is a clear stone with a waxy exterior. It displays conchoidal fracturing and various forms of chalcedony were used to create knives and arrowheads in the Stone Age. It will have a hardness of 7, the same as other forms of silica.

Chalcedony is often used to refer only to the pale blue variant found in many places. I have no idea how that ended up being the definition of the common term but you’ll see it used that way frequently.

Definitions of cryptocrystalline silica types are a subject of debate at times. Whether a given stone is chalcedony or agate or jasper may depend on who you’re asking. That said, regardless of the term used, agate, jasper, and a few others are simply more varied forms of chalcedony.

Chalcedony is almost never entirely clear, it will have color or inclusions trapped inside of it. As the base mineral for many of the most popular stones in the rock trade, it’s an important part of the hobby. Understanding it is something every rockhound should strive for.

What Types of Chalcedony Are Available?

The most common stone sold as chalcedony is a pale blue, banded form of the mineral. This form of chalcedony can be quite expensive for higher-grade material and it remains a common gemstone used in jewelry. Uniformity and more saturated color are the name of the game when it comes to pricing.

But there’s far more to the family than that.

There are three main types of chalcedony found in the stone trade:

- Chalcedony- Used for lightly included, transparent material of different colors.

- Agate- Strict definitions require an agate to include banding (ie: fortification agate) but the term also includes several varieties of transparent, heavily included, clear chalcedony such as moss and plume agates.

- Jasper- Applies to red, opaque cryptocrystalline silica in its original meaning but currently can be applied to any form of chalcedony which ends up being opaque.

Agates and jasper are both their own subjects, with tons of varying forms between them. They’ve also been covered separately in our guides to jasper and agate respectively.

Those are the definitions we’ll be working with as we go further into the article.

Chalcedony itself isn’t as simple as it looks. There are quite a few different variations with their own names.

The following are all recognized varieties of chalcedony:

- Blue Chalcedony- Often simply called “chalcedony.” This form of chalcedony is often banded, resembling a pale blue agate.

- Chrysoprase- A green variation of chalcedony. It’s colored by nickel oxide and is distinct from the other major form of chalcedony.

- Chrome Chalcedony- A bright green chalcedony variation. This stone is colored with chrome, naturally, and is quite rare.

- Heliotrope/Bloodstone- A dark green chalcedony that is colored with hematite inclusions that appear as red spots on the exterior of the stone.

- Carnelian- A red form of chalcedony. It’s sometimes referred to as “carnelian agate” when banded, leaving some room for interpretation when the stone is being classified.

- Onyx- Black and white banded chalcedony. Used for cameos in the past, the black part is commonly cut out to be used as a black stone in jewelry as well.

- Gem Silica- A sky blue, transparent variant of chalcedony. This is the most expensive form and it’s the highest possible grade of chrysocolla. It is distinct from blue chalcedony.

- Flint- An important stone by any measure. Flint is high-grade chalcedony with heavy inclusions resulting in an opaque color. These inclusions rarely disrupt the conchoidal fracture of the material.

- Chert- A subject of much debate, chert is usually regarded as low-grade flint or boring jasper depending on whether you’re asking a knapper or lapidary about it.

- Petrified Wood- Petrified wood is usually some form of chalcedony, consisting of a silica replacement for the original wood. Some petrified wood is comprised of other stones, usually opal, instead so it’s not quite accurate to say all petrified wood is chalcedony.

These are the primary forms of chalcedony found, but there are other colors out there.

One form that is found very commonly is very lightly colored, often off-white or brownish. It serves an important role in the rock trade that we’re going to look at.

How to Detect Dyed Chalcedony

One of the most common things to see at booths, shows, and shops across the country are brightly colored stones sold as agate or chalcedony. These stones often have high color saturation, interesting formations, and solid colors.

You’ll see the same with beads and other small pieces put together for jewelry.

None of these are natural. The light-colored chalcedony described above is the material used as the base for these dyed stones. This isn’t a new process, either.

Indeed, at one point in the past, it was common practice to use light-colored chalcedony as ballast for ships. This was transported from the New World back to Europe, where the stones were further treated.

In the past, this was most often a black dye. The stone was then sold as onyx, which was much more valuable than the common agate nodules brought back from the Americas. This was a high-profit affair since transporting the heavy stones was essentially free.

Currently, dozens of different colors are available in dyed agate or chalcedony. The colors of the rainbow and more have been unlocked through the use of penetrating dyes.

Spotting these is a good first lesson for a new rockhound. The following signs usually show that chalcedony is dyed:

- Color Saturation- Few pure pieces of chalcedony have a high saturation of color. Large pieces, such as geode slices, with high saturation throughout are almost always altered stones.

- Concentrated Color in Cracks- Dyes feed through the stone by capillary action. This means that cracks and fractures in the rock will absorb more dye and stand out. For a good example see Dragon’s Vein Agate, a dyed form of chalcedony that’s been cracked through thermal shock.

- Uniform Colors- If all the bands are the same sort of hue (ie: purple, pink) then you’ve got a dyed agate on your hands. Most natural agates have different hues in them.

These stones are often sold as “natural chalcedony” when you find them as cabochons or beads. And… they are, but there’s definitely been some human work behind their final appearance in the shop.

Bottom line is that brightly colored chalcedony with a reasonable price tag isn’t real. The various strongly colored varieties (ie: gem silica, chrome chalcedony) are very expensive and rare. They’re sometimes faked, but it’s less common than you’d think since people buying them tend to be aware

Where Can I Find Chalcedony?

Chalcedony emerges in various forms almost everywhere. If there’s sedimentary stone around, chances are that there are at least some nodules of agate and jasper mixed in. Limestone, in particular, often hosts an astounding array of different chalcedony types.

It would be accurate to say that chalcedony can be found in most creek and river beds across the US. There are some places they can’t be found but they’re few and far between.

There are a few places to find the more pure versions of chalcedony in the US and Canada if you know where to look. It’s impossible to put together a comprehensive list in an article this size, but the following should give you a head start on finding some if you’re hunting:

- Blue Chalcedony- Northwestern Nebraska

- Chrysoprase- California, Oregon, Washington

- Heliotrope- California, Oregon, Washington, Georgia, Pennsylvania

These are far from the only locations, but as a general rule, these are all good sources of the indicated stone. I’ve seen examples from every state, there are at least a few chert nodules in most corners of the world.

Due to the fact that chalcedony is virtually everywhere… there’s not a whole lot of specifics to give when it comes to hunting. Just do the same s you’d do for any other stone.

And, most importantly, have fun while you’re in the field!

Chances are that you already have a few examples of this cryptocrystalline silica on your shelf, but there’s always more in the field. Why not hit your local honey hole or search for a new one?

- Online rock and mineral club for collectors of all levels!

- Find community with like-minded rock and mineral enthusiasts.

- Monthly Giveaways!

- Free Access to Entire Digital Library of Products (annual memberships)