If you dig your own rocks and minerals, you’ll eventually have to clean them. Just using running water rarely cuts it, but the key is to remove dirt and build up without damaging the stones.

There are a lot of ways to clean rocks and minerals, and each specimen is its own unique case.

Let’s hop right in and I’ll show you the basics of getting your specimens into tip-top shape for displays and exactly how to clean rocks and minerals.

Related:

A Word About Hardness and Mineral Composition

Which approach is viable for an individual stone depends on the chemical makeup of the mineral and its hardness.

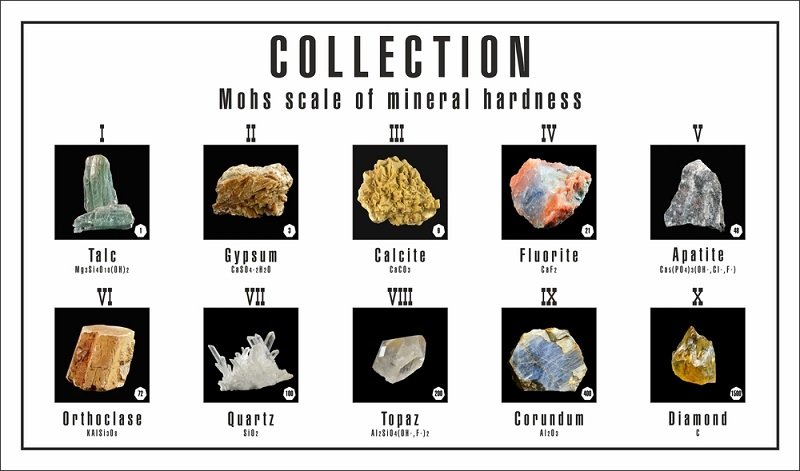

Every rockhound should have a good idea of the Moh’s scale. It’s important for most aspects of the hobby. Soft stones don’t do well with harsher methods of mechanical cleaning, even a brass brush can seriously damage a specimen of calcite for instance.

Just make sure you know how hard the stone is. Anything under 5 shouldn’t be cleaned abrasively.

Chemical cleaning of stones is used to get the best out of specimens.

It can also lead to ruined specimens.

For the most part, you can consider silica minerals inert when using chemicals. Very few things will dissolve it, which makes it easy to chemically clean off any minerals that are on the crystals.

On the other hand, calcium minerals will often dissolve entirely in an acidic situation.

There are countless other reactions to be aware of. My advice is simple:

Always do your research on the chemical composition of your specimens before using any chemical cleaning method on them.

Getting Your Hands Dirty: Mechanical Cleaning Methods

For most people, just being able to break off the dirt around a specimen is enough. Stones have a tendency to be harder to clean than you’d think, and it can be frustrating. The following ways of cleaning are a good approach, and most people will use a combination to get their rocks shining.

First Approach: Soap, Brush, and Water

The first thing to try is a scrub brush and a bit of dish soap. You can clean them under running water, but I’ve found that a small bucket is usually the best approach.

Avoid cleaning stones in your sink. Once or twice may not hurt, but the dirt and sand that comes off your rocks can build up in the pipes. You’ll make your plumber’s day.

But you’ll be the one with the bill.

Just get the water a bit sudsy and brush as hard as you can. Use a nylon brush initially, there are very few stones that can be damaged with a normal scrub brush. I like to use a big brush initially and then an old toothbrush to get the smaller spots afterward.

It’ll get off the majority of the dirt on the exterior of the stone and knock loose any broken bits, but it’s rarely enough.

Brushing and Probing the Dirt

Dental probes are perfect for picking dirt and mud out of the small holes and pockets in a stone. A bit of attention can get dirt that you didn’t even notice on the first pass.

For very compacted material you can also use a wire brush.

Stick with brass. Theoretically, steel won’t scratch most silica materials and harder things like corundum. In practice, theory shouldn’t be relied upon.

Brass brushes shouldn’t be used on very soft mineral specimens, you’ll scratch the surface and possibly do other damage.

That said, steel brushes aren’t a bad idea for the exterior of stones you’re planning on cutting. A few scratches is no big deal since they’ll be on the edge of the slab and it’s a very expedient method of cleaning deep dirt.

Consider Ultrasonic Cleaning

Ultrasonic cleaners maker short work of dirt, and even some mineral buildup, but you’ll need to be careful using them. They have a bad reputation in some circles, and I’ll cover why in a second.

Ultrasonic cleaners function by vibrating a container of cleaning solution at a very high rate. This creates cavitation bubbles in the solution which strip out materials. The tiny bubbles can get into even the tightest crevice and remove any contaminants on the stone.

That same deep cleaning is why they can be problematic for cleaning mineral specimens.

Ultrasonic cleaners should only be used on hard minerals, and preferably those without any visible fractures on the interior. The cavitation generated in cracks can cause stones to break if you’re unlucky.

Likewise, porous minerals and organics will break down quickly in an ultrasonic cleaner. The GIA has some good guidelines for gemstones that can be applied to mineral specimens.

Ultrasonic cleaners are the most thorough mechanical cleaning method but they’re also the riskiest.

Sandblasting

Sandblasting is best reserved for very hard specimens with a lot of matrix that needs removal. It can affect the surface of most minerals with ease, so you’ll need to do more cleanup before the piece is ready.

In other cases, it’s a miracle worker.

Use glass bead as your abrasive media, rather than quartz or garnet sand. You’ll do less damage to the exterior, and in many cases, you may avoid doing any damage at all.

It’s expensive, but if you’re regularly cleaning specimens it’s a great tool to have around.

Air Scribes

For large material removal, it’s hard to beat an air scribe.

These little tools are sold as marking devices for use on metal. They’re just a tiny pneumatic chisel, and if you have an air compressor they’re inexpensive.

They should be used carefully. An air scribe is essentially a miniature jackhammer, and a little bit of inattention can do damage to your specimens.

The use of air scribes is situational, but they’re the best tool to remove large amounts of material to reveal the desired specimen.

Spot Cleaning Guns

Spot cleaning guns are used for clothing, but the high-pressure spray of water is great for cleaning up minerals.

They’re a bit specialized, but not super expensive and they won’t take up a lot of room.

Use them for the initial cleaning of specimens, they’ll help you figure out what else you need to do to keep the specimen in top shape. In many cases, these may be the only tool you’ll need.

Chemical Cleaning Methods at Home

Before we go any further, I advise you to be very cautious when using any sort of chemicals to clean your specimens.

Some of the chemicals used can cause serious injury if mishandled. If you’re not confident you can use these methods safely then you can give them a pass.

While some techniques exist for specific minerals, chemical cleaning is mainly used with silica-based minerals like jasper, agate, and quartz varieties. This is because they’re inert as far as most acids are concerned.

If you’re cleaning things like calcite or flourite, the below will actually destroy your specimen. Always do your research before cleaning a mineral. Even household cleaners can damage some stones.

First Up: Chemical Safety

You’re going to need to have the following on hand to begin:

- Safety Goggles-Not glasses, they need to surround your eyes entirely.

- Rubber Gloves-A small splash can lead to big pain, get a decent fitting pair so you’re not tempted to do anything with them off.

- Respirator- Even if you’re working outside I recommend using a respirator when working with chemicals like muriatic acid.

Make sure that you have something to neutralize any acids with on hand. A big bag of baking soda is the easiest to acquire. You’ll dump it on any spilled acid to neutralize it before cleaning up.

Always have safety contingencies in place. A spilled bucket can be a disaster if you’re not ready for it.

Likewise, you should always perform chemical cleaning outdoors or in a very well-ventilated room.

While it has some risks, you can do quite a few chemical cleaning techniques at home. Approach with caution, but the end quality of some specimens can be improved by a lot if you’re willing to go through with it.

The Slow Approach-Cutting Calcium Minerals With Vinegar

If you’re edgy about using chemicals, you can still use a slower approach to clean off a lot of calcium build-up and other easily removed minerals.

Cover the specimens in vinegar and allow them to sit for a few days. Most of the time you’ll be cleaning up a quartz crystal or other silica mineral using this method so a brass brush can be used to remove loosed minerals.

Vinegar can take a few days to work fully. The diluted acetic acid still attacks calcium, but not as much as other acids, the main reason to use it is simply that it’s much safer than most other methods of cleaning.

Tried and True Calcium Removal With Muriatic Acid

Muriatic acid is available as a masonry cleaning chemical, where it shines at removing stains from bricks and concrete.

It can also rapidly break down less desirable minerals that are included with your specimen. The majority of the time these are calcium-based minerals, often showing unattractive growths on the rest of the crystal. Others might form a deep-pocketed limestone matrix on an agate nodule.

It’s a simple process:

- Clean your specimens of surface dirt and loose matrix with your preferred method.

- Thoroughly dry your crystals or nodules before placing them in a plastic or glass container. Do not use metal containers when working with acids. Pyrex is the preferred material but not required.

- Cover the specimens with muriatic acid, taking care to avoid any fumes or spilling.

- Check on your stones, the calcium minerals will actually dissolve so you don’t need to do anything else to remove them.

- When the specimens look clean, remove them with rubber gloves or tongs and then run them under water from a hose. Take 30 seconds to 1 minute to flush any acids from each sample.

- Prepare a solution of baking soda and water, place the stones in this overnight to neutralize any leftover acids in cracks or seams.

Disposing of the acid is easy in most places. Instructions are clear, the acid needs to be diluted to 5% or less or completely neutralized before being disposed of down a drain.

Remember that you always add acid to water, not the other way around. So, if you’re diluting the acid with 10x the volume with water you should add the acid to the water. Doing it the other way around can generate heat and create a dangerous situation.

You can also add baking soda until the solution stops fizzing. Do this progressively to avoid any problems with heat, but when it’s stopped fizzing the acid is mostly inert and can be disposed of down the drain.

I recommend going the neutralization route rather than just pure dilution, but both are acceptable under Federal standards. Check state laws if you’re unsure, as some jurisdictions may have more stringent rules.

Targeting Ferrous Oxide Contamination

Finding formations of quartz with a stubborn, orangeish stain is common. In most cases, it’s caused by the formation of rust due to small amounts of iron in the mineral.

In some specific cases, crystals may have a thin layer of iron oxide formation. This occurs mostly in specific deposits of quartz or amethyst but removing the layer greatly improves the specimen.

You can use most anti-iron cleaners to attack it. Naval Jelly is a favorite, and it works just as well on stones as it does ship bodies.

It’s not a bad route to go before an acid dip if you’re wary of chemicals.

- Online rock and mineral club for collectors of all levels!

- Find community with like-minded rock and mineral enthusiasts.

- Monthly Giveaways!

- Free Access to Entire Digital Library of Products (current and future products)*