Concretions are a bit of an oddity in the world of rocks and minerals. They’re one of the things I’ve seen trip up beginners over the most, and it’s simply because they don’t fit in with what most of us know about rocks. In reality, they’re perfectly natural and they have an easy explanation.

So, let’s take a closer look at concretions, first up…

What is a Concretion?

A concretion is a hard mass found within layers of sedimentary stone. They’re generally round in shape, and each type tends towards one form or another.

You shouldn’t confuse a concretion with a nodule. Nodules occur as minerals different from the surrounding layers, while concretions are largely composed of the same sediment as that which formed the sedimentary rock they’re housed in.

Concretions cause all manner of confusion for amateur rockhounds and fossil enthusiasts.

More than one person has been disappointed to break open a concretion and find the interior wasn’t what they were expecting.

And more than one person has eagerly taken their “dinosaur egg” to the local university only to be informed it’s just another form of sedimentary stone taken from the area.

They’re certainly an oddity, no matter how you look at it. For many, that’s enough, but the truth is that their formation offers a lot of clues about the local area’s geology and they’re certainly interesting enough in their own right.

How Are Concretions Formed?

Concretions are formed through the precipitation of minerals in sediment before it hardens. Essentially, they became mineralized before the rest of the surrounding rock. Concretions form early on in the sedimentary stone cycle if they’re present.

Remember that a sedimentary stone is comprised of a mass of sediment, such as sand or clay, that’s been compressed over time. It’s often the second stage in the life cycle of rock since sediments tend to be formed from minerals that erode out of igneous stones.

Quite often there’s a nucleus in there, a little bit of something different from the surrounding sediment that mineralized more easily than the surrounding environment. This is often organic matter, an ancient leaf or shell for instance. Not always, however, as siderite concretions have been found in Europe which formed around unexploded ordinance from World War I as the exterior has corroded.

There are two types of growth patterns displayed by concretions.

Pervasive growths occur when the host sediment is penetrated by another mineral which effectively cements them together. For example, water rich in calcium carbonate penetrating silica sand can create a concretion as the water repeatedly evaporates and leaves behind its calcite.

Concentric growth occurs when the exterior of a material continues to grow. This can occur when, for instance, an iron oxide like goethite precipitates out of a nearby water source and repeatedly forms around a nucleus. These are commonly spherical and can be seen frequently in sandstones.

What’s inside a Concretion?

What’s inside depends on the type of concretion. As a general rule, those that were formed by concentric growth should have something in the center. Those which are pervasive in growth will often simply be harder than the surrounding rocks.

For fossil hunters, concretions are always an exciting opportunity. Some may contain fossils in the center, and it’s common for them to be broken open in the field to take a look at what might be inside.

There won’t be something visible in every concretion, but they’re a boon for fossil hunters who learn to recognize them and how to crack them open.

Types of Concretion and Their Contents

There are hundreds of different concretion types around the world, each unique to the area that they’re from. That said, there are also some broad types that are more commonly seen. Let’s take a look at some of them.

Septarian Nodules

Septarian nodules are actually a concretion. They’re also among the most interesting since the interior minerals have cracked through the exterior which forms a mottled coloration. This polishes up well and they can sometimes be seen cut as polished slabs or even cabochons.

While their origin is a bit controversial, the contents aren’t. Inside of a septarian nodule is a little bit of something that originally caused them to begin to form a sphere. Septarian nodules are primarily found in carbonate-rich mudstones. Essentially, the ball of mud cracked at some point and allowed the infilling of the nodule with calcite, generally yellow from iron content. Aragonite is also found in these nodules, often as a brown band around the exterior calcite.

Moqui Marbles

A curious iron oxide concretion is found in the Navajo Sandstone of Southeastern

Moqui Marbles are the subject of extensive study, especially since similar balls have been discovered on Mars.

It appears their formation began during a seismic shift in the region about 20 million years ago. The raising of the Colorado Plateau created small fractures and allowed the intermixing of iron-rich water with methane and natural gas. The precipitated iron formed around a single grain of sand, causing them to grow in a concentric manner over time.

Kansas Pop Rocks

Curious iron sulfide concretions found in Gove County, Kansas. These are formed of pyrite or marcasite, creating a roughly spherical concretion. They’re called pop rocks because they have a tendency to explode when thrown in a fire. When struck, the iron sulfide generally sparks as well.

These appear to have been formed by the precipitation of iron sulfide within the pelagic goo that forms in certain oceanic areas. While they occasionally enclose pieces of bivalve fossils, they don’t contain fossils as a nucleus.

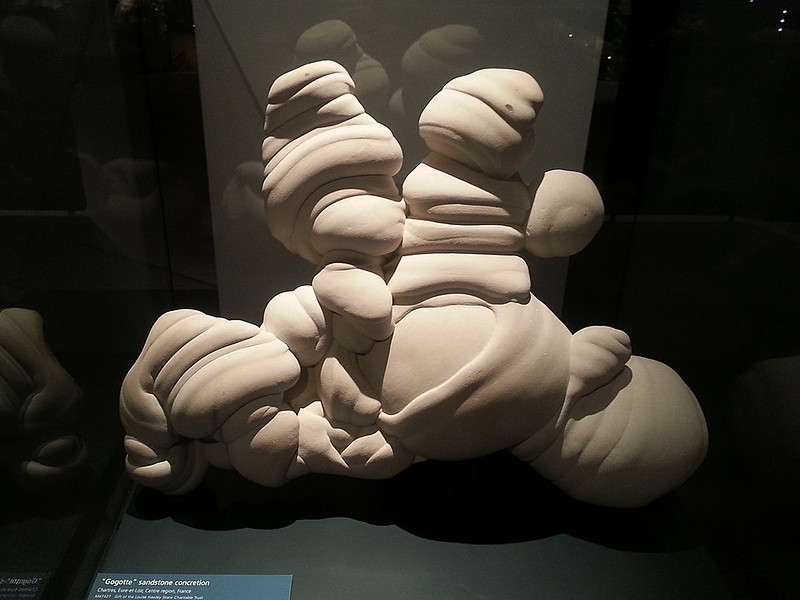

Gogotte

These are some of the odder concretions, and it has to do with their pervasive growth. The above-described types all grew concentrically, while the Gogotte emerged from pervasive growth. They’re found in only one place in France.

Gogottes often resemble modern sculptures, being composed of small spheres and strange organic shapes not often seen in stone that’s unworked by human hands.

Their formation occurs when calcite-rich, superheated water penetrated the fine silica of the local sandstone before it had fully turned to stone. As the waters evaporated, the calcite was left behind and it binds the white particles of the sandstone together.

These particular concretions are quite rare, and their unique sculptural form makes them highly desirable… and expensive.

Should I Open My Concretion?

Many rockhounds have a concretion around somewhere, whether they brought it home knowingly or unknowingly. Opening them up can be a controversial affair, but in the end it’s going to boil down to the person involved.

While some concretions may contain fossils, not all do. That can make it a bit of a gamble if you choose to open them up and like the exterior form.

If you do choose to open them up, it’s a fairly simple matter. Just strike around the outside of the concretion with the pick portion of a rock pick repeatedly until it breaks. Generally, about half of the stone will fall off, revealing whatever was in the nucleus. Ammonites are often found in concretions, for instance.

Not all types of concretions have even a chance of containing something inside. I recommend against cracking things like Kansas Pop Rocks or Moqui Marbles simply because there’s never going to be anything inside.

On the other hand, if you’re in the field and know fossils are in the local rock, it can be a great surprise to crack one open and find an interesting fossil.

- Online rock and mineral club for collectors of all levels!

- Find community with like-minded rock and mineral enthusiasts.

- Monthly Giveaways!

- Free Access to Entire Digital Library of Products (annual memberships)