Among the various fossil agates, Turritella agate is a standout stone. This chalcedony variant comprises small fossils held in a tough shell, meaning it’s one of the few fossils that can be cut and polished. For that reason, many people have found it to be among their favorite stones.

So, let’s take a deeper look into Turritella agate, including the prehistoric origins, where it can be found, and some tips for working with the rough if you’re of the lapidary bent.

What is Turritella Agate?

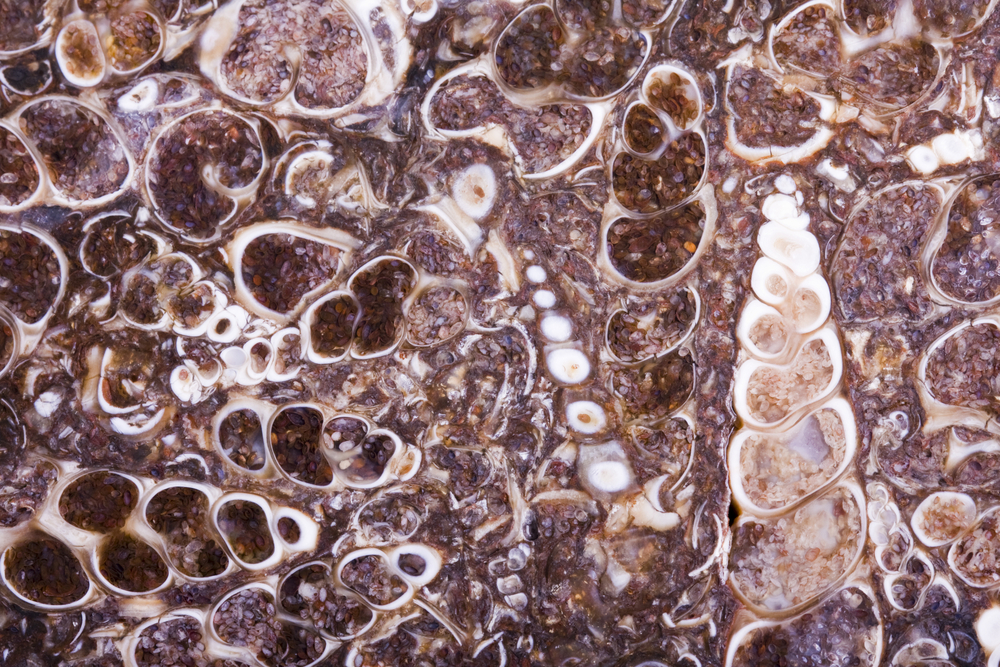

Turritella agate is a brown-to-black chalcedony that contains small white-to-grey inclusions. These inclusions aren’t just a trick of mineralization, instead, they’re actually the prehistoric shells of snails.

What Kind of Fossils Are in Turritella Agate?

The area where they’re found, the Green River Formation, was originally thought to be the remains of an ancient sea. The name of the stone derives from an ancient genus of marine snails, the Turritella sp. This genus still exists today, bearing distinctive shells that resemble a spiraled horn.

In actuality, the area was found to be an ancient lake bed. The species responsible for the shells contained within the chalcedony is Elimia tenera, a now-extinct species of freshwater snail. There’s a very slight difference in the angle of the shell’s opening that allows for distinctions between the two species.

But, as tends to happen with stones, the name stuck despite this discovery. On very rare occasions you’ll see it referred to as Elimia agate by pedantic sellers, but as a general rule it’s almost always labeled Turritella agate.

On occasion, other small bits of fossils can be found. These may be from ancient plant life or fragments of shells from other gastropods and mollusks.

How Was Turritella Agate Formed?

This agate appears with various different levels of silicification. The best material is hard throughout and will take a high polish, while some of the “lesser” bits of Turritella agate may be best off as display specimens without an attempt at a mirror polish.

The details of the snail’s shell are often well-preserved, allowing you to see the individual whorls and even the internal chambers once the stone has been cut. Often the fossils will be around the outside of the rough, making it even more apparent that these are indeed fossilized snails.

The story of how this fossiliferous agate was formed is familiar to those who know about agates. The snails originally died and fell to the bottoms of the ancient lake they called home, roughly 50 million years ago. Over time, the sediment occurring in the lake buried the shells, but the snails were so prolific in the lake that there are entire layers of sediment almost entirely made up of their shells.

After being sufficiently buried, hot water rich in silica filled in the gaps. It’s generally thought that this material was actually a hydrated gel, which later cooled and formed the chalcedony that the shells are trapped in.

Chalcedony is a cryptocrystalline form of quartz and its polymorph moganite. That means that the crystal structure is only vaguely apparent even at the highest magnifications. In essence, it ends up being smooth and “one piece” rather than quartz which grows into six-sided, pyramid-topped points.

Not all of the material is sufficiently silicified for cutting, if you’re going to go find or purchase some see below for tips on making sure you’ve got the right rough for lapidary use.

Where is it Found?

Turritella agate is primarily found in the Green River Formation in Wyoming. This formation is comprised of several ancient, dried lakes that are scattered around the borders of Wyoming, Colorado, and

For the more modern tastes, the usual place where people hunt for the agate is along Wamsutter Ridge, which starts roughly 8 miles south of Wamsutter, Wyoming. It’s said to be found on both sides of the road at this point.

Where to Look

The Green River Formation is comprised of about a dozen different types of sedimentary stone. Turritella agate is generally only found in a few of these, so it can help to narrow your search by making sure you’re digging in the right bedrock.

The majority of Turritella agate is found in shale or sandstone units within the larger Green River formation. These are a good place to start, but remember that only a small portion of them will be silicified enough to be used as lapidary material.

Tips for Working With Turritella Agate

Turritella agate, at its best, can be worked roughly the same as any other agate. Start with 80 grit for pre-forming the stone after slabbing and trimming, and proceed as you usually would.

If you’ve never worked with agate, a common progression is 80 grit, 200 grit, 600 grit, followed by 1200 grit. I generally hand polish up to 5000 grit from there before using a felt wheel impregnated with cerium oxide paste for a final polish.

Zam also works well for agates, although it’s a bit slower.

I should note that sometimes small bits may not be hard enough to take a fantastic polish. In that case just do your best, having a few dull spots is completely normal unless you have very high grade material to begin with.

Selecting Your Rough

While Turritella agate isn’t exceptionally rare, the best rough isn’t a common sight. There are a few ways you can judge the stone before you purchase or take home your rough.

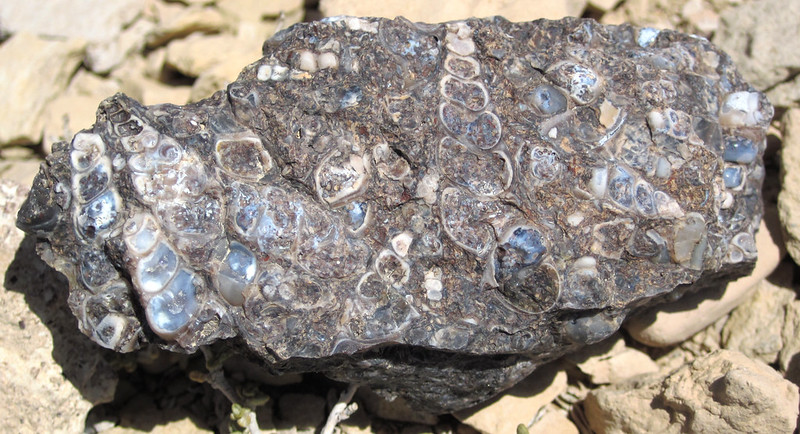

The most important is to make sure that you can see the fossilized shells of the snails on the exterior. If you’re collecting in the field then try to wiggle the shells and make sure that they’re well cemented into the matrix. Heavily silicified material should feel 100% solid, if there’s a wiggle then it may not be suitable for lapidary use.

The other big thing to keep an eye out for is the color of the matrix. On average, the darker the exterior of the stone, the better it will be on the inside. It’s usually a good indicator that the interior is heavily silicifed and has a darker background.

Generally, people favor backgrounds that are closer to black when looking at pieces for decorative use as well.

Slabbing for the Best Effect

There is a right way and a wrong way to cut Turritella agate. Similar to tube agates, when you cut the stone the wrong way you’ll end up with just a round inclusion, but if you cut along the shells you’ll find that you get the whole shell.

While some of the shells may be different in orientation, generally the majority of them will be facing in one direction. This allows you to slab the material and see the interior of the snail shell, creating a much more interesting visual effect.

The rough will generally have shells on the exterior since it’s separated from a layer of sediment. It’s often tempting to cut it vertically since it’s a bit easier, but you should always cut horizontally along the shells.

You may still end up with a few “spot” inclusions but the material will also open up and show you the highly desirable fossils in all their glory.

- Online rock and mineral club for collectors of all levels!

- Find community with like-minded rock and mineral enthusiasts.

- Monthly Giveaways!

- Free Access to Entire Digital Library of Products (annual memberships)