There are many forms of agate, but perhaps none quite matches the beauty and mystery of fire agate. Fire agate has a legendary reputation on two counts. Among collectors, it’s prized for iridescence and detailed botryoidal inclusions. Among lapidaries, it’s known to be one of the hardest materials to cut properly.

So, let’s dive in with this guide to fire agate.

What is Fire Agate?

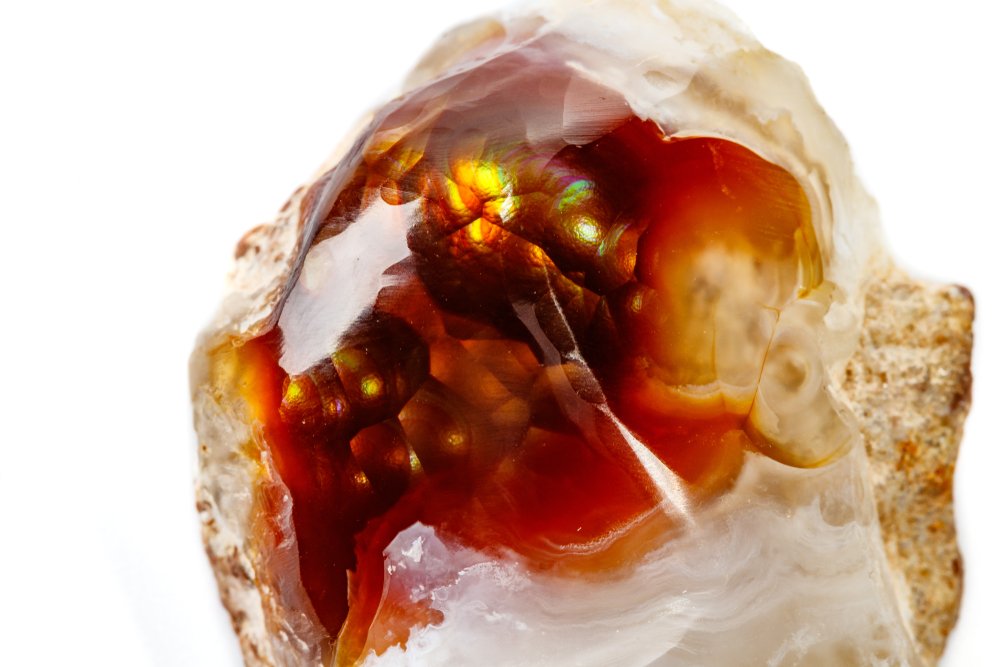

Fire agate is a clear chalcedony that contains layers of goethite or limonite alternating with silica and creating a spectacular optical effect.

Fire agate is a clear chalcedony that contains layers of goethite or limonite alternating with silica and creating a spectacular optical effect. Rough material is relatively inexpensive. But cut, high-grade stones are both expensive and scarce due to the difficulty inherent to cutting and polishing the stone correctly.

Fire agate is, at its base, a form of included clear chalcedony. The inclusions that typify fire agate are botryoidal formations inside the stone, resembling small spheres intersecting with each other. These formations will display a play-of-color as the stone is turned in the light, creating an effect similar to but distinct from that found in precious opal.

Fire agate is quite rare and only found in a few locations worldwide. The good news is that most of them are in North America, so American rockhounds won’t have to leave the country to have a shot at bringing some home.

Fire agate is graded to some degree. Low-grade fire agate will often be primarily red and white banded chalcedony, with some small formations of fire agate contained in it. High-grade fire agate is simple: a good play of color, clear internal formations, and no “regular” chalcedony included with the piece.

Indeed, it can be hard to tell from a picture if a particular high-grade piece of fire agate was cut en cabochon or carved down to the iridescent layers. Both of these techniques are used to make fire agate suitable for jewelry.

Fire agate’s display is the result of microscopic layers contained in the stone. Essentially, silica and layers of a couple of different ferrous minerals repeat themselves in very thin layers, scattering light without quite blocking it. The responsible iron oxides are goethite and limonite, both common ores of iron used in steel production.

Fire agate is an expensive stone… if you want to buy it cut in advance.

Here’s the thing, I would never diminish the lapidary arts but most stones work in roughly the same manner. You smooth out the surface, grind the angles, and then round it off before polishing. We’re ignoring things like undercutting here, but they’re still minor in comparison to what you face with fire agate.

With fire agate, that’s a great way to end up holding nothing of value after cutting away the fire.

Where To Find Fire Agate

Fire agate isn’t found in many places. As far as I can tell it only naturally occurs in certain parts of North America with nothing quite like it showing up anywhere else in the world.

This highly sought-after stone is found in the following regions:

- Southern, inland California

- Arizona

- Central Mexico

The deposits are scattered across public and private land in the usual mishmash that makes life difficult for rockhounds. You’ll need to be sure that any area you’re digging in is legal, and remember that regulations change wildly from California to Arizona.

Some places, like the Black Hills Rockhound Area in Arizona are specifically laid aside for rockhounding. Other places, like Opal Hill Mine above Palo Verde are on private land with all the difficulty that entails. The latter was actually a fee dig site until recently when it was closed indefinitely.

In California, the stone is known to be found in the Mule Mountains, and there are regions there that make it easy for public collection.

While the stone isn’t found elsewhere, it’s scattered across a broad section of the Mojave desert in the United States. More deposits are surely out there and the Mojave is one of the most amazing places to rockhound in the country, so you’re not likely to go home empty-handed at any rate.

Fire agate is often seen as small, botryoidal clusters when the pockets have been broken into by erosion and other natural action. If you find a place to actually dig searching for it is much the same as any other seam agate, you simply follow the vein as far as possible to remove the material.

- Online rock and mineral club for collectors of all levels!

- Find community with like-minded rock and mineral enthusiasts.

- Monthly Giveaways!

- Free Access to Entire Digital Library of Products (annual memberships)