Hidden in a corner of Ohio is a big secret, some of the most beautiful flint in the world. This flint deposit was a major source of tools for the indigenous people who once populated this area, and to this day it finds use by both lapidaries and modern knappers.

But what exactly is it, and where is it found? Check out our guide to Ohio flint to learn the answers!

What is Ohio Flint?

Ohio flint is a microcrystalline form of quartz, generally regarded as an impure form of chalcedony. Chalcedony is a mixture of both quartz and its polymorph moganite, but the crystals intertwine at such a small level that even a microscope can have trouble discerning the exact structure of the crystals.

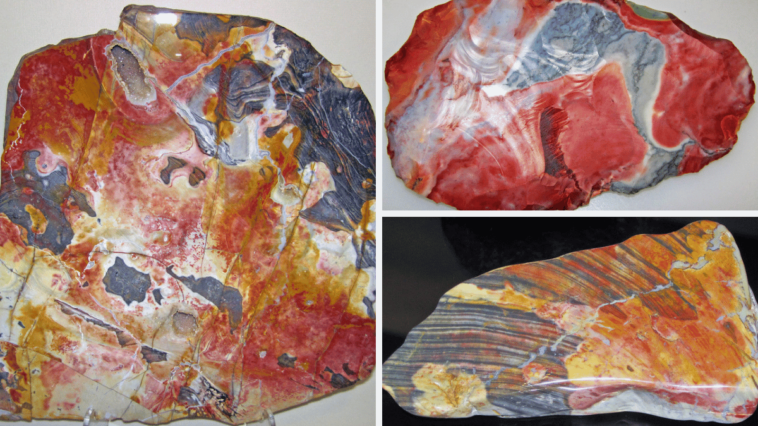

Ohio flint has a reputation for being a tough, durable source of tools but it’s also available in a wide range of different colors that make it a favorite to this day. You’ll see it sold as “rainbow flint” on occasion. While trade names make things difficult for collectors, it’s certainly an accurate description in this case!

The History of Ohio Flint

Ohio flint occurs within large deposits of marine limestone in the state of Ohio. Limestone is a sedimentary stone comprised of calcium carbonate minerals, particularly aragonite and calcite.

Most of these minerals are derived from organic sources. In particular, corals and some microorganisms. The skeletal structures left behind by these sources accumulate over time as they’re broken down, creating grains of sediment. In other cases, the grains may come from the shells of mollusks and calcium-rich algae.

This form of bio-generated mineral accumulates on the bottom of the sea due to one of the few constants of our planet: erosion. Over time, it buries itself increasing the amount of pressure due to the sheer mass of it all. We’re talking about geological time scales here. Once pressed together, the result is limestone.

Cherts, jaspers, and flint are common finds in limestone. They seem to occur when silica-rich water begins to flow into the stone. Limestone is porous, which means it absorbs water and allows it to seep into voids. The silica is deposited in these voids and over time forms into different forms of microcrystalline and macrocrystalline quartz.

Roughly 15,000 years ago, glacial action scoured the much softer limestone from the surface, while the flint itself remained intact underneath the glaciers.

Ohio flint has a particularly long history of human usage. In fact, it appears that it was known and actively quarried as long as 11,000 years ago. Its tool usage is well documented, with thousands of known artifacts hailing from the region. It appears at distances far from the location it’s found, meaning that it was most likely a trade good or that people were willing to travel very long distances on foot in order to use the material.

In fact, there are records of Ohio flint being traded for native copper from the area we now call JUpper Michigan by the Hopewell tribe. It was also documented being traded for shells from along the Gulf of Mexico and mica from the areas that make up the states of North and South Carolina.

In fact, it’s even been found as far away as Louisiana and Colorado.

It was even of use to the Europeans. The high-grade flint found in the area was often made into gun flints. These precisely shaped bits of flint were integral to the use of flintlock firearms, which only become obsolete after the widespread occurrence of percussion cap firearms in the 1830s.

These days, it’s considered to be the state gemstone of Ohio. Lapidaries favor the colorful varieties for carvings and cabochons, and it’s still highly regarded among those who continue the long human tradition of flintknapping.

Defining Flint, Chert, and Jasper

The various microcrystalline and cryptocrystalline forms of quartz are highly contentious. People will call them by different names, primarily depending on their background.

As a general rule, these stones are all chalcedony with various impurities. A rough guide to their definitions would be the following:

- Chert- A geological term for most forms of chalcedony, especially when opaque. It’s primarily associated with larger formations of impure chalcedony, but it’s also used for nodules and other smaller formations on occasion.

- Flint- Generally any chert or jasper that’s been used for tool creation will be referred to as flint by archaeologists. Flint is also used on occasion to describe more chemically pure forms of chert/jasper. It’s not a requirement, but flint is often translucent in thin slices.

- Jasper- A gemologist and lapidary term for any opaque microcrystalline quartz that happens to catch the eye. Jasper is traditionally brightly colored, but it’s not a highly scientific term and the only requirement is complete opacity.

While someone like myself would likely describe brilliantly colored Ohio flint as a jasper if I didn’t know the origin, you’d find that archaeologists would use flint and most geologists would refer to it as chert.

What Makes Ohio Flint So Special?

There are two main properties that set Ohio flint apart from other flints across the country.

The main one is that it’s incredibly dense for a flint. This makes it easily knappable, and also means that it will hold an edge better than those which aren’t quite as compacted.

That doesn’t mean it’s unbreakable. Far from it, Ohio flint is very brittle but that actually only adds to its usage as a tool. Like all knappable stones, Ohio flint displays a conchoidal fracture.

Conchoidal fractures occur in stones without a natural cleavable plane. They sometimes, but not always, point to an amorphous or cryptocrystalline nature. These fractures are cone-shaped, often with “waves” that emerge from the point of percussion. This is handy for tools, since small fractures can result in a very thin cutting edge.

The other thing that makes this flint stand out is the chemical impurities that give it dramatic coloration. While much of the flint in Ohio is grey with white streaks, in some specific locations it can be found with brilliant colors, just as impressive as any stone traditionally referred to as a jasper.

There’s one more small thing that makes it special: Ohio flint occurs in massive veins which means that it’s a readily quarriable material.

Is Ohio Flint Worth Anything?

The value of Ohio flint largely depends on the composition of the material and how far it’s been worked before purchase.

Less colorful rough can be found for a few dollars per pound, while the highly colored material may range up to $20 or more per pound. Slabs can be found for anywhere from $6-$40+ dollars depending on the grade of flint and its coloration.

Cabochons tend to be on the costly side. While not prohibitively expensive, cabochons with good color can compete with most semi-precious stones in price. Pieces that are particularly colorful or unique can fetch high prices when done well.

In particular, bright colors and druzy pockets are big factors in the final value of a slab or cabochon.

Where To Find Ohio Flint

It depends on what you mean by Ohio flint. The grey or mildly colored material can be found in almost any limestone across the entire state.

What most people are referring to when we speak about Ohio flint, however, is material from Flint Ridge. This is an eight-mile-long section of a huge vein, near Hopewell Township in Licking County. It’s roughly three miles north of the town of Brownsville.

The area contains a museum, the Flint Ridge State Memorial, and the Flint Ridge State Preserve.

Is It Legal to Collect Ohio Flint?

You’re not allowed to collect Ohio flint from public land, including the memorial and the nature preserve in the area. You’re also not allowed to collect from the various ancient quarries that dot the hiking trails in the area.

Fortunately, not all of the land is private.

The most common place that people head to is Nethers Farm, which is located smack dab in the middle of the area. The woman who runs the place generally charges about $5/person, and the flint itself will run you $1-2 per pound. You can find more details on the Nethers Farm Flint Ridge page on Facebook.

There are also the so-called “knap-ins” which are events for flintknappers where the material is available. These are run by a gentleman named Roy Miller who may have more details on collecting in the area as well on his website.

For the less adventurous, various forms of the material can be found on eBay, Etsy, and other online stores where stones are bought and sold.

Tips for Working With Ohio Flint

Ohio flint is a great material to work with. I stumbled across some roughly five years before writing this article and quickly found it to be easy to work with, whether for knapping or lapidary use.

The material is exceptionally fine-grained, which means that it’s very hard (ie: 7 on the Moh’s scale) and takes a great polish. The only issue is that slabbing the material can be quite slow due to its density. That’s not a knock against it, the agates and jaspers I favor are all the same way when they’re high-grade.

As a general rule, I treat the material the same as agate for lapidary use. Slab, cut, grind starting at 400 grit and run to 1000 grit before polishing with cerium oxide. Diamond paste will actually give very good results if you work through the various grits as well, but I’ve found it unnecessary to achieve a near-mirror polish.

Because of the hardness of the material, it’s easy to slice it into ¼” slabs for low dome cabochons or arrowhead preforms. Many types of flint are better cut at ⅛” to maintain integrity. I’ve found the material to be mostly crack-free but your experience may vary.

One other thing to keep in mind is that vugs are fairly common in this material. Keep an eye out for them when slabbing and cut accordingly.

Selecting Ohio Flint Rough

Selecting rough is easily the most important part of the process for lapidaries or knappers who want particularly colorful points made from the material.

Anyone who has cut a jasper knows that the outside of the nodule may not be able to fully describe the interior. The same rules hold true here, but there are a few things to look for.

If you’re able to collect your own from Nethers farm, I’d suggest bring a copper bopper (a piece of copper pipe capped on one end with lead melted into the cap) or antler bopper. A quick flake taken off can show the interior more accurately.

Otherwise, look for rarer colors like purple or green on the exterior. These impurities commonly occur alongside more brilliantly patterned material and are a good indicator that the material is going to be extra beautiful once it’s been opened up.

Heat Treatment for Knapping

While it’s not necessary, heat treatment is common among flintknappers.

The basic idea is that it dries out the small amount of water in the material and creates a more homogenous internal structure. This makes it easier to get clean flakes, and even Ohio flint will get some benefit from the process.

There are some pros and cons to this process, so consider them carefully if you’re actually going to use the tool.

The material will have a sharper edge, but it will be less durable. This is great for things like arrowheads used for hunting but it’s a big problem for tools like knives and scrapers which will need to be touched up more often.

It can also improve the appearance of the material.

It’s relatively easy to do at home. The usual method is:

- Spread out your material on a baking pan.

- Set your oven to ~200°F.

- Allow the stones to heat for 2 hours.

- Raise temp by 100°F to 300°F.

- Hold temp for an hour.

- Raise the temperature by another 100°F.

- Hold the temperature for 1 hour.

- Raise temperature by 50-80°F (Roughly 450-480°F)

- Hold for two hours, then shut off the oven and allow it to cool. They may take 2-3 hours to cool enough to be handled so be patient.

There are various recipes that you can find online, but the one above is specifically tailored for Ohio flint, especially the higher grades. Do not try to cool it down by using water. The thermal shock can cause the stone to shatter.

In general, you need to raise any chert, flint, or agate to at least 400°F to remove the water content. Other methods include using kilns and even burying them under a campfire, but most people will have access to an oven and it’s the easiest way to do it.